This is an opinion piece written by Charlie Bedard, COO of OpenRefactory. Charlie reflects on SAST practices based on his years of experience.

Programing languages are the “carpenter’s tools” for software developers. Just like a good carpenter would not use a chisel as a screwdriver (OK, I have done that in an “emergency”), it is good practice to choose the best tool for each job.

But what constitutes the “best” tool? Early in the evolution of programming languages, there was a steady push for languages that were intended to guide programmers to avoid common errors. “Structured Programming” and “Object Oriented Programming” approaches were all presented as the solution to the inevitable problem of so many bugs being introduced into the code via simple programming errors.

Living with C

Having written code in a variety of languages, I first began serious development in C in the early 1990’s. On one hand, C is considered “powerful”. That is true when looked at through the lens of having precise control over the use of the system resources. But that same power makes it dangerous.

I was fond of saying that using C was like handing a loaded gun to a toddler: it was just a matter of time before something bad happened.

Not surprisingly, roughly coincident with the arrival of C came lint. Also developed at Bell labs, it was initially a tool to help with portability of C[1]. I used lint as much as possible during my C development days. But it was tedious. It generated tons of warnings and I found myself torn between either ignoring the warnings by turning them off, or by throwing casts around like candy. Both of those were bad ideas and I eventually established coding standards with my colleagues to avoid the worst noise.

Much later, lint was displaced by the emerging arrival of Static Analysis (SAST) tools. The good news is that such tools were far better than lint in terms of detecting potential coding problems. And they could also help identify places where emerging C coding standards were being broken.

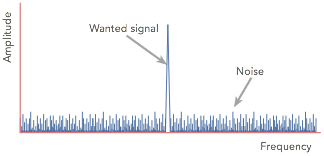

Nevertheless, inasmuch as these SAST tools were far better than lint in terms of isolating issues, they exhibited a similar problem: noise. In their effort to identify problems, they produced a pretty high rate of false positives. That is, warnings that we “might” have an issue.

Nevertheless, inasmuch as these SAST tools were far better than lint in terms of isolating issues, they exhibited a similar problem: noise. In their effort to identify problems, they produced a pretty high rate of false positives. That is, warnings that we “might” have an issue.

By this time, I was managing a large team of developers all of whom were “required” (as is common in large software companies) to use SAST on all major builds. I appreciated the value these tools brought in helping ferret out potential problems, but the developers found the triage process tedious and intrusive. After all, the developer who wrote the code was not the best person to decide if a warning should be heeded or not. So, each development team was involved in triaging their teammates’ software. Not surprisingly, many “warnings” got disabled to reduce the noise and the tedium of the review.

As a manager of a large development team, it was a case of making a call between the time it would take to not only triage the warnings, but also to remedy the large set of, what many considered “trivial” problems. Who wants to devote precious engineering time to resolve the many idiosyncrasies of C coding?

The flip side of taking that position was the chance that one of those seemingly simple oversights might, in fact, turn out to be a serious problem. Sometimes those innocent-looking coding flaws might become serious security vulnerabilities. I certainly remember the hours and days diagnosing nasty system bugs that eventually were traced to a simple error caused by mismatched integer types in C or a buffer overrun.

Which is why I became involved with OpenRefactory’s intelligent Code Repair (iCR). A skeptic at first, once I learned what it could do in not only detecting common programming errors, but providing the corrections, I saw that it tackled the most onerous part of fixing the code. Why ignore the warnings, or turn them off, if a tool would correct them for me?

Much better to not have to deal with all that noise!

[1] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lint_(software)